New York city based artist Amelia Marzec has been working on a project Weather Center for the Apocalypse since 2015. The work is presented during Climate Week in NYC, opening taking place on September 20, 2016 at United Nations Plaza. The artist has created an ongoing and evolving Weather Tower installation, which handles a theme of change in the environment and culture where we live in. Weather Center for the Apocalypse is an alert to an uncertain future as it predicts those “changes that could affect the autonomy of citizens in the event of disaster”. According to Marzec, the project offers alternative perceptions to the media-driven forecasts we constantly encounter, and takes seriously the fears and superstitions that we as community may have. Recently, the project was on display at Sixth Extinction Howl at Billings Library in the University of Vermont in Burlington, VT.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: How did you find weather? It is there all the time, but to become a derivative and subject for art, do you find it is common at all?

Amelia Marzec: Currently there are a lot of artists doing work either directly or indirectly on the influence of human activity on climate change. I have seen a few other weather projects since starting the Weather Center for the Apocalypse. Everyone on earth is participating in this story right now, whether they are aware of it or not.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: Tell about the background for your project, which will also materialize during Climate Week in New York.

AM: The Weather Center for the Apocalypse began during an anxious time when I was in a relationship that was failing, at the same time that my Grandfather’s health was failing. It was a moment of knowing that these things were going to end, while not knowing exactly when that was going to happen. I needed to prepare and put things in perspective: what would be the most outrageous ending? The world could end, of course. With the current focus on climate change, it didn’t seem that far off.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: Have you always been future oriented, foreseeing the future, as apocalypse might imply?

AM: Yes. My current work began a number of years ago, when I lost all of my hearing in one ear due to a tumor. I began to focus on the reality of daily communication failure in my life, and to pay more attention to the physical objects that make up our telecommunications infrastructure: our phones, our internet, our radios, and other devices. I began building objects to avert possible future disasters of communication in our society. The Weather Center for the Apocalypse continues this work by becoming a news media center for a pre-apocalyptic world.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: How about the narrative part of your Weather Center for the Apocalypse project, in which the visual implements a strong narrative element, what do you want to say about it?

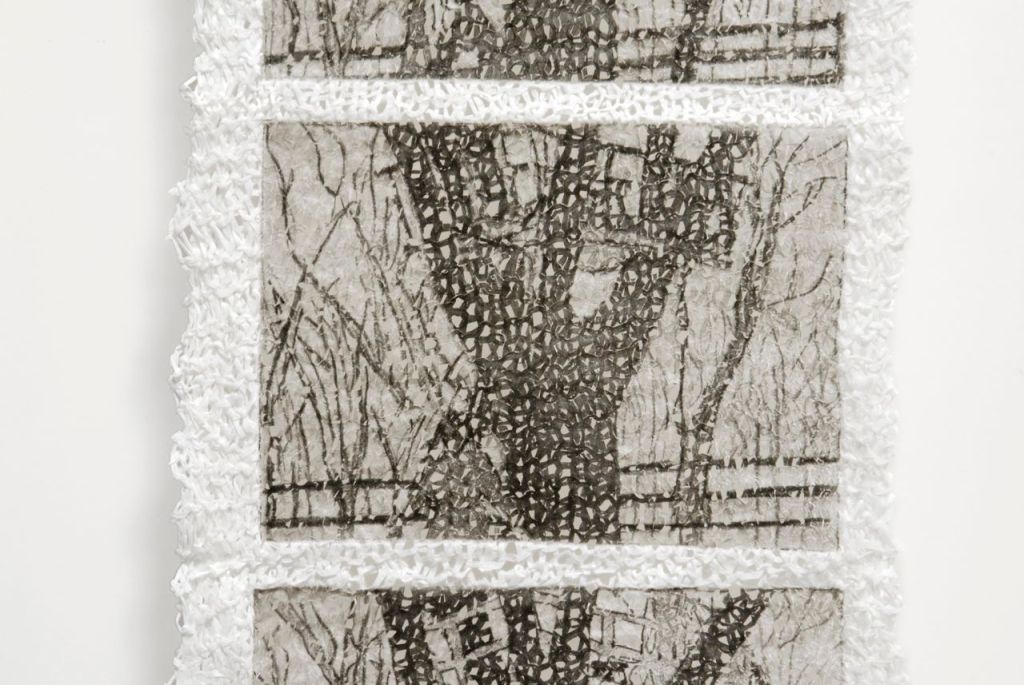

AM: The story of the Weather Center unfolds over time as the project is built and refined. It began by providing forecasts to STROBE Network, a news network that was broadcast from Flux Factory in 2015. News and weather reports that were both practical and fantastical fed a daily apocalypse warning system. However, it has become clear that the Weather Center needs to be prepared for complete telecommunications failure, so the Weather Tower, which is a functioning weather station, was built mostly from salvaged materials that I gathered in my neighborhood. It collects local weather data so we don’t need to rely on major news sources. Predictions, fears, and anxieties are collected by interviewing local residents, and severe warnings are broadcast over a short distance with an FM radio transmitter.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: Where did you install the Weather Tower before, and how did those environments alter the direction?

The Weather Tower has traveled to different locations in New York to collect weather data and predictions from residents, including Industry City with Creative Tech Week; Governor’s Island with FIGMENT festival; Sag Harbor with Wetland, a fully sustainable houseboat; and Long Island City with Flux Factory and the Artificial Retirement exhibition. Being outdoors tends to trigger people’s memories more of changes that are happening on the earth. I’ve been caught in the rain a few times now, which has forced me to become better at weatherproofing the work.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: Since you will have the UN presentation, what expectations do you have for it. Is it possible that the work will gain more global visibility with the location?

AM: There are some meetings that week at the UN about climate change, so it would be really nice to continue those conversations in a public place, as it affects all of us. I would also let passers by know about Climate Week. This type of artwork tends to happen one conversation at a time, so I don’t expect it to be a global phenomenon. Hopefully I can collect some interesting predictions.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: Does the work read a label climate change art, do you think that art can be a vehicle towards a better understanding on what is happening?

AM: Yes, climate change is one of the major themes of the Weather Center for the Apocalypse. I do think art is a vehicle towards better understanding of the issues, and I also think that is one of the responsibilities of an artist.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: You have been connected to Eyebeam in New York City, what has this education and community meant for your creative thinking?

AM: I’m currently an Impact Resident at Eyebeam, working on our conference Radical Networks. The conference brings together artists, educators, and technologists to discuss the future of alternative networks in the context of community. This could mean experimental social computer networks, local community and rural networks, network security, uses of networks for activism, and the overall question of who owns the network. The community at Eyebeam is made up of some of the most forward-thinking people on the future of art and technology, and it is an honor to be among them. Seeing how other artists live and get work done has given me the confidence to pursue these projects, in addition to expanding my thinking about the work itself.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: What do you think a notion artistic research designates, a process that goes beyond a merely presentation to include research on a specific subject?

AM: It depends on the context, sometimes it simply means searching for images or text to be used in a project. But it should mean practice-based research, which has more depth in that the projects are leading a conversation, which happens in the context of previous writers and theorists. There’s other types of research where you’re mostly talking about artwork, but not making it. I’m a very hands-on person so I’m letting the work lead for now.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: It is so interesting how you relate to technology with a nostalgic wibe. There seems to be also a feature of old electronics and low tech involved in the making. How do the objects make you inspired?

AM: My previous project, New American Sweatshop, is a working model of an electronics manufacturing factory for a post-industrial economy, using our trash as a natural resource. I had gotten frustrated with building activist projects that were only possible for very privileged groups of people: people who could afford to buy technology, and had the education to know how to build it. I was also getting parts from international companies. During hurricane Sandy, there was no way to get supplies, as the roads were closed. So I started the New American Sweatshop to source parts locally from the resources that we had, which turned out to be our trash. It’s not so much nostalgia as necessity, knowing what we’d have to do to build communications infrastructure in a disaster scenario.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: You have discussed a role of the digital as something that might alienate us from connecting to one another. Should we go back in time, beyond the internet in our human communication, or do you think there is something else, which is a possible way to go?

AM: We need to use the current digital technology as a tool to organize and meet up in person. We need each other as human beings, and we will never be able to duplicate the experience of being together in the same space, despite advances in technology.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: What are the philosophies which you rely upon, and make references in you work?

AM: I’ve always been very much into DIY culture, having grown up in the 80’s and 90’s.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: One strong sensibility which comes across in your approach is feminist art, or a community of women making societal art. You have been featured in conjunction to A.I.R. Gallery in Brooklyn that promotes the women’s voices. Would you like to say something about this special connection?

Women are not on equal footing worldwide, so anything that serves to amplify women’s voices and give them confidence in their work is something I appreciate. Being together to have this discussion and forming our own networks is key. It’s possible that I’ve gotten more opportunities through connections with other women than with men. The idea of women competing with each other is outdated; we are more effective when we collaborate, and that is something that I see younger women doing more and more.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: Does VR resonate with anything you are interested in? Can we save the world with the idea of VR offering alternative perspectives?

AM: I’m both fascinated and frightened by VR. I don’t believe it will save the world. Having different perspectives is always helpful, but people have to be open to them. Whatever happens, we have to keep working on our own morality.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: Where do you wish yourself going next in terms of plans?

AM: I’d like to build out more of the Weather Center, and I’m looking for support in order to do that.

***

Amelia Marzec was born in Red Bank, New Jersey, and went to college at Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers in New Brunswick. She came to NYC to attend the Design and Technology MFA program at Parsons in 2003, and has lived in the city ever since.

Check out artist website: http://www.ameliamarzec.com/