Aimee Lee is an artist, papermaker, writer, and the leading hanji researcher and practitioner in the United States. With paper, she makes thread, sculpture, books, drawings, prints, garments, and installations. Aimee Lee’s background as a performing artist and musician carries traces of paper as sets and costumes. Her installations are artistic research on paper and sound. She has pursued a career with traditional Korean hanji, coming up with new aesthetic concerns and techniques for her artistic practice. As a scholar, she is author of award-winning book, Hanji Unfurled (The Legacy Press).

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: You are a musician, a performer with live violin. How did you start creating performances onsite, including your own installations, manifesting set designs and creating costumes? Did everything start with music?

Aimee Lee: My early aspirations were to become a concert violinist, but I learned in college that I was not serious enough to devote the requisite hours of practice and study. However, I still loved music and wanted to stay close to musicians, so I continued to play and my first jobs were in music administration—bringing music to people who did not have access, or bringing people together through music.

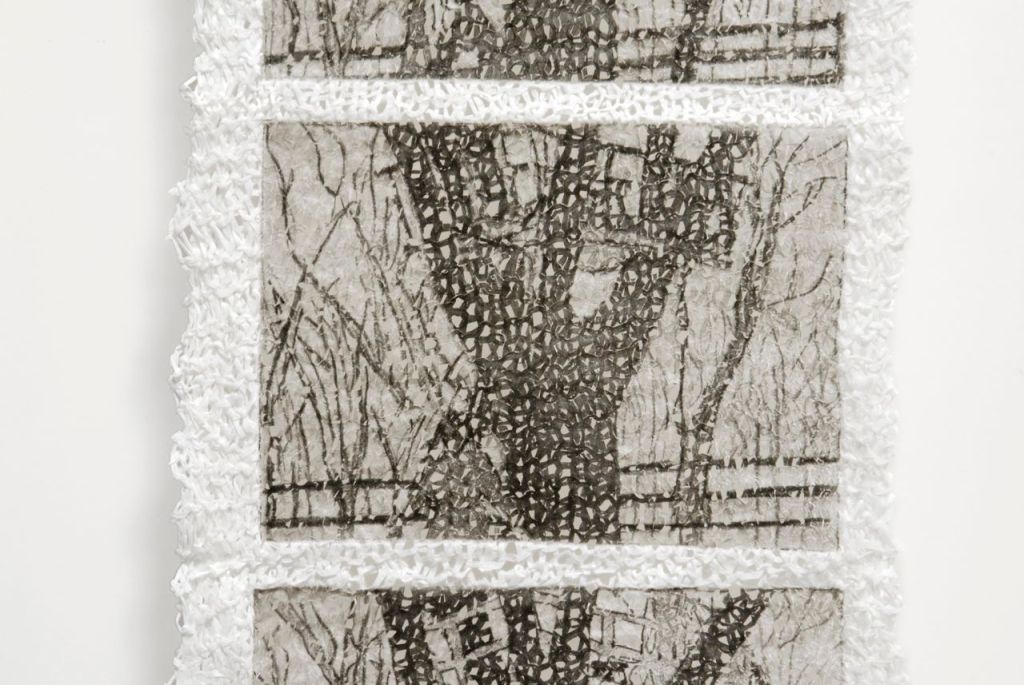

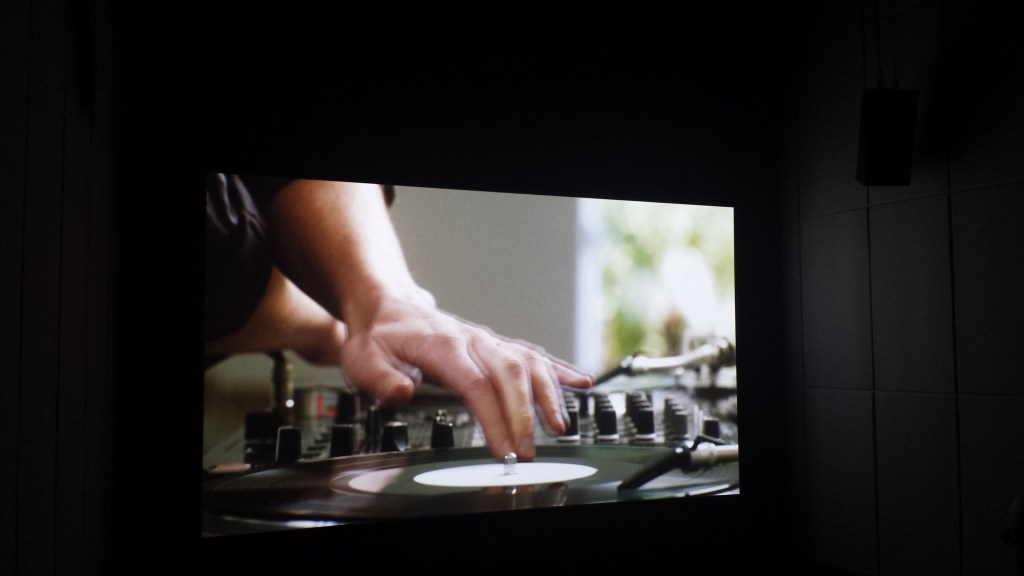

When I moved to Chicago for graduate school, I entered an interdisciplinary program that encouraged combining different media, especially performance. It was a book and paper program, but I was interested in the intersection of books and performance. Once I began to make paper, the connection between paper and performance was so compelling that I created installations that were dependent on paper that I made. The performances, which almost always included sound from my violin, activated the installations.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: Some of the live performances, which you composed and put together implement almost haunting kind of sound that responds back from the architecture of the venue, and then audience is stretched to interactive listening and feedback, where did you get the ideas to make these works?

AL: Mostly, I studied classical music, but later learned improvisation and jazz. The heart of what I have always loved to do is rooted in improvisation, whether or not I was aware of it. Human communication, which sound and music are, has always fascinated me, so I wanted immediate feedback and interaction with my audiences. In Chicago, I was influenced by performance residencies with Aaron Williamson and Greg Allen, and by Julie Laffin.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: Now, we can perhaps say that you have become a master of hanji, the Korean traditional paper making. Where did you find the enthusiasm to start exploring it, and how did it come about?

AL: While I studied papermaking history in the graduate school, I noticed that it began in China, moved to Korea, and then traveled to and flourished in Japan. Most of the existing research in English on East Asian paper was based in Japan, and I was unable to find much about hanji (Korean paper). I grew up at a time and place in the US where people always tried to guess my heritage, but they could only imagine that I was Chinese or Japanese. This sense of Korea being overshadowed affected me deeply, so I felt a curiosity about Korean paper history. My Fulbright research in Korea uncovered an entire history and culture that fascinated me on all levels, as an artist, a researcher, a Korean American, a person in the world. After my return to the U.S., I felt a strong responsibility to share what I had learned. I would never call myself a hanji master, but will always be a steadfast hanji ambassador and artist (read Aimee Lee’s exhibition review in Firstindigo&Lifestyle)

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: Is the knowledge of making hanji widespread in Korea today, how about the new generations and passing down this historic form that goes back hundreds of years?

AL: Korea has similar issues to the U.S. and other cultures where the current knowledge of traditional craft by the general public is quite limited. It is not a priority in contemporary life, so not many people in Korea are aware of the process of making hanji and its impact on Korean history. There are less than 25 paper mills remaining in Korea, and very few have serious apprentices, because it’s not an easy living. In a world where you could live and work in an urban center with all the amenities you need, why would someone decide to live in a rural area doing manual labor for very little money? There are no good incentives to do the work, even if you believe in continuing an ancient and important tradition.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: How sustainable is the process, could you tell about the ecological aspect of the paper making?

AL: Papermaking on a small scale (meaning individuals or families who are in business) in Korea is ecologically sustainable, though it may not be financially so. The main raw material is the paper mulberry tree, which is cut each year. This coppicing practice encourages the plant to grow back every year, so the same plant can produce material for over 20 years. These are not trees in the way Western minds think of hardwood lumber: they are tall and skinny, almost shrublike, and cutting them down does not kill the plant. The traditional methods of processing always used plant materials so that production byproducts were easy and not toxic to dispose of or reuse. The bulk of the energy that goes into making hanji is human energy, which means that the process is very labor intensive but has a very light ecological footprint.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: Is it correct that Hanji derives from nature, or implies a closeness to it?

AL: Hanji is made from plants, and could never have been invented without a human closeness to non-human nature by observing the possibilities of certain species and experimenting over time. Dorothy Field, artist and author (my favorite is her book Paper and Threshold) writes beautifully about how certain plants long to become paper, and all they needed was the human hand to let them reach that state.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: Can Hanji accessories, or clothing, be compared to textiles, or is it irrelevant?

Paper and textile have a very strong connection, aside from each being able to be transformed into the other. The first paper was made from hemp cloth, and hanji can be cut, spun, and woven into cloth. Hanji has been used to make clothing, and today’s contemporary designers and manufacturers are including hanji into their textile production.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: You are teaching as well, could you tell about the workshops and education aspect?

AL: I mentioned before that sense of responsibility to share knowledge about hanji to a much wider audience. Part of this is from a conservation instinct, out of a fear that hanji is disappearing. But most of it comes from a joyous instinct, out of my love for this material that is so endlessly versatile. I always knew that handmade paper had great range, but even after almost a decade, I continue to find possibilities for hanji. If the substrate was not impressive, I would not feel compelled to promote it. However, I want people to know about hanji as an option, so that they can have another tool in the toolkit. This means that I teach a range of workshops, from preparing fiber to making hanji to manipulating it by hand. I travel continually to spread the word, in the hopes that eventually hanji will become as familiar as other papers, and that paper itself can be regarded on the same level as canvas, clay, metal, glass, wood, and so on.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: The aesthetic form of Hanji art and folk art influences your making, how do people receive these traditional objects, which you are making today?

AL: Most people don’t know about the lineage of the objects, so the responses are mostly of wonder—they are amazed that my pieces are made of paper in the first place. This provides an opening to share the stories of their historical use, and illuminate the ways that humans have always made objects that are not only useful, but embedded with meaning. Some have asked if I am interested in using the techniques to make much more contemporary ‘looking’ art. I have wanted for years to extend crafts like jiseung into installation and larger work that goes past the original shapes and functions of their predecessors. The issue is that the time and labor that it takes to make one piece is so great that I could only go in that direction if I had a very long and uninterrupted stretch of time to work. However, I am gratified to see that some of my students are moving in that direction after learning about hanji and its applications.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: What other materials do you use today in the making of your art?

AL: For the longest time, I have been very strict about using hanji whenever possible, or other handmade papers. My thread box is always full of different paper threads I have made, though I use cotton, linen, and silk thread to sew my hanji dresses. I also use the raw materials that make these papers, such as the cooked bark before it is beaten to a pulp. I use mostly natural dyes and finishes, which add color, structure, and protection to the paper. Last year, I collaborated with Kristen Martincic on a paper and ceramic installation, and recently had a couple of jewelry metals artists help me with additions to my paper ducks at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts. I’m interested in continuing this last investigation further.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: What is fascinating about your use of paper is its multiple dimensions from small objects to books. Your own writing and art (illustration) is sealed into these art books. Tell about the books, which you have made, how did the stories develop?

AL: Books came first for me, before paper. I was making artists’ books at Oberlin College while studying with Nanette Yannuzzi Macias, which was a game changer. It was a way to combine writing, drawing, storytelling, and all kinds of other media into a form that felt very familiar and yet new. I don’t remember when I started to draw comics, but like improvisation, it was something that came naturally to me. I always thought that the point of being able to make my own books was the ability to create all of my own content. Most of my books contain original writing and stories that come from my own life experience, literature that I love, and the immediate present moment—whether an emotional space or an actual time in history that could be marked in the news cycle.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: Do you travel to Korea to get new ideas and exchange?

AL: I am able to get back every several years, whenever I am funded. However, because of the distance and difficulty of making enough time to visit (I prefer going for longer periods of time), it’s not a journey I make often. Certainly it is inspiring, but it is a challenge as well because the expectations of me as a Korean American woman can be stressful.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: Often you hear that there is a division of thought between Eastern and Western approaches or philosophies. Do you feel you are bridging the gap between east and west in your practice, or do you think about these questions?

AL: This idea comes up often and much of my work can be seen as bridge building between cultures. However, I do my best to stay away from the reductive nature of “East/West” because it sets up an automatic “Us/Them” mentality that can become dangerous. My life experience of feeling reduced to a single word, automatically, because of how I looked, keeps me aware of the unconscious instincts we have to categorize everything. I prefer to present my scholarship and artwork as being rooted in and inspired by many different traditions and cultures. It’s impossible for me to work any other way because I was born to immigrant parents and always lived between at least two disparate cultures.

The “east meets west” cliché is one I particularly dislike, as if it has just happened, and as if there are only two monoliths in the world. It also comes from the point of view of a certain place being the center or more superior, which is problematic. Most cultures around the world have been in contact with each other for centuries, so cross-cultural understanding is not a new thing or an anomaly. Rather, it’s the norm.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: Where do you see yourself as an artist and educator in the future?

AL: My goal is to build a new hanji studio for myself, where I can work, make paper, and teach independently, while continuing to travel to teach and exhibit. I want to train apprentices in this new space so that I can increase the number of people who can support hanji. There’s at least one more scholarly book left in me as well, so I look forward to finding the ideal setting to properly research and write it. All of this will be unlocked, I think, once I find the right place for myself to be.

… … …

Check out Aimee Lee on web: http://aimeelee.net/

Her artists’ books can be found under the Bionic Hearing Press imprint from Vamp & Tramp.