Nozomi Rose is a rocking Japanese woman artist, who has a lot to say about the women’s role in the fine arts. From traditional Japanese Nihonga to Western artistic techniques, she uses fingernails to add dimension to the paintings. She was trained in painting at Cornell University and earned an MFA at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. The focus for our discussion is on diversity of artistic practices. We listen to her plans from organizing a conference in New York City, where artists and scholars who have more than one practice get to present their work and share knowledge on how one discipline informs the other. She is publishing an e-book in Japanese on hybrid art teaching and learning for Tatsu-zine Publishing. Her exhibition ‘Dai Dai’ will open in New York at Japanese Embassy on October 2nd. This exhibition will feature her latest paintings of multiple techniques, along with her other works.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: We had a discussion about patriarchal Japanese art-institution, could you explain that a bit?

NR: Haha. Are we really starting out our interview with this question? I was talking about the wife of Ikuo Hirayama, one of the most important Nihonga painters in Japan. Ikuo Hirayama is a Hiroshima-A bomb survivor, served as the President of Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music (a.k.a Geidai) twice, and a synonym for Nihonga, so I would say he is a Japanese version of Jackson Pollock. Well, sort of…Hirayama paints landscape and is known for Silk Road paintings. Everyone in Japanese art knows his name. His wife Michiko Hirayama entered the same university with Ikuo and was the top of their class. Ikuo was the second. Michiko, however, gave up on her painting career when they got married because their best man told her that having two painters in one household would not work. Michiko took the advice and stopped painting, and then, Ikuo truly climbed to the top of the field. It sounds similar to Lee Krasner now I think about it. There is a Japanese idiom “breaking one’s brush,” which typically means “stop writing stories,” but Japanese painters see that the words symbolize a female painter’s marriage with a male painter in Nihonga. Michiko’s episode is an urban folklore among Japanese painters worldwide. I heard this story for the first time when I was studying painting in Paris, France!

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: You are using both western means of creating art and Japanese traditional Nihonga in your art, how naturally this came about to you as an artist and when?

NR: Oh, you mean, I use Nihonga paints with acrylic medium on canvas and you see it as unusual? That is a very good point. The fact is that, though, many Japanese painters trained in Nihonga use this method in New York. Also, Nihonga pigments are heavy because their particles are much larger than western pigments, so I can’t really use gum arabic for this, like you do in watercolor. I can’t mix it with oil painting medium because oil paints cure through oxidation, and oxidation changes the colors in Nihonga pigments. These are scientific sides of why and how it came to me. The technical diversity creates the differences in visual effects in western and Japanese paintings. I am curious to see how Nihonga paints react to various western painting mediums in my work. I might try it with oil paints at a later time. I have increasingly been attracted to casual ways of making paintings, so the color change may be okay for certain types of work that I will create in the near future.

You may be asking me about the conceptual side of the work. For me, using Nihonga paints is one way of “citing” Japan in my work, but this is not the main theme I promote in art. Personally, making art has more to do with erasing my own identity as Japanese rather than emphasizing it. I was told at an early stage of my artistic career that I should stay away from quoting Japanese art materials or Japanese visual languages for my own work because they can never make my art original. For example, I can never be unique by copying Ukiyo-e patterns as art because many people have seen those. I have never trained in Nihonga; learning Japanese traditional painting never attracted me. When I was still in Japan, I was studying oil painting; I liked Japanese oil painters such as Ryuzaburo Umehara who studied with Pierre-Auguste Renoir. I enjoyed seeing the world through the lens of Japanese artists influenced by the western aesthetics.

I also liked the works by westerners influenced by the Japanese aesthetics. This included Impressionists and conceptual artists like Daniel Buren, so I went to Paris in 1999. I even went to Monet’s house in Giverny, but you know…he had a strong collection of Japanese woodcut prints and that was the secret! It was a bit unfair that I had to travel all the way from Japan to France only to witness that Claude Monet was a big fan of Japanese art. Daniel Buren, on the other hand, might not be familiar with Japan although his work looks very Japanese, especially the installations with color stripes.

Do you know there was no art in Japan until Ernest Fenollosa came and made it happen with Okakura Tenshin, who established Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music and was a curator at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston? Okakura Tenshin was Fenollosa’s assistant and both of them worked for the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. People who say that the Japanese Constitution was written by the United States would probably claim that Americans created Japanese art, but I am not a historian.

So my short answer is that it has always been on my mind. However, inserting something very Japanese directly into my own artwork, which I have long been resisted, came to me only when the Japan Tsunami Earthquake Disaster happened.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: The collaboration between Fenollosa and Tenshin is very moving, and kind of tells us how the world of artists has always been connected. Do you feel you are mediating between East and West with your art, or do you think that it is stereotypical to make this opposition?

NR: As a visual artist, color is my “language.” I would like color to mediate between east and west in my work, so my answer is yes and I feel there is no way for me to escape this. I am certainly interested in mediating between Japanese and American visual effects and aesthetics. Japanese art has borrowed elements from Indian and Chinese art, so it is the idea of East. I think the question is more about “how” I am doing it. I am watching how my art can mediate both east and west.

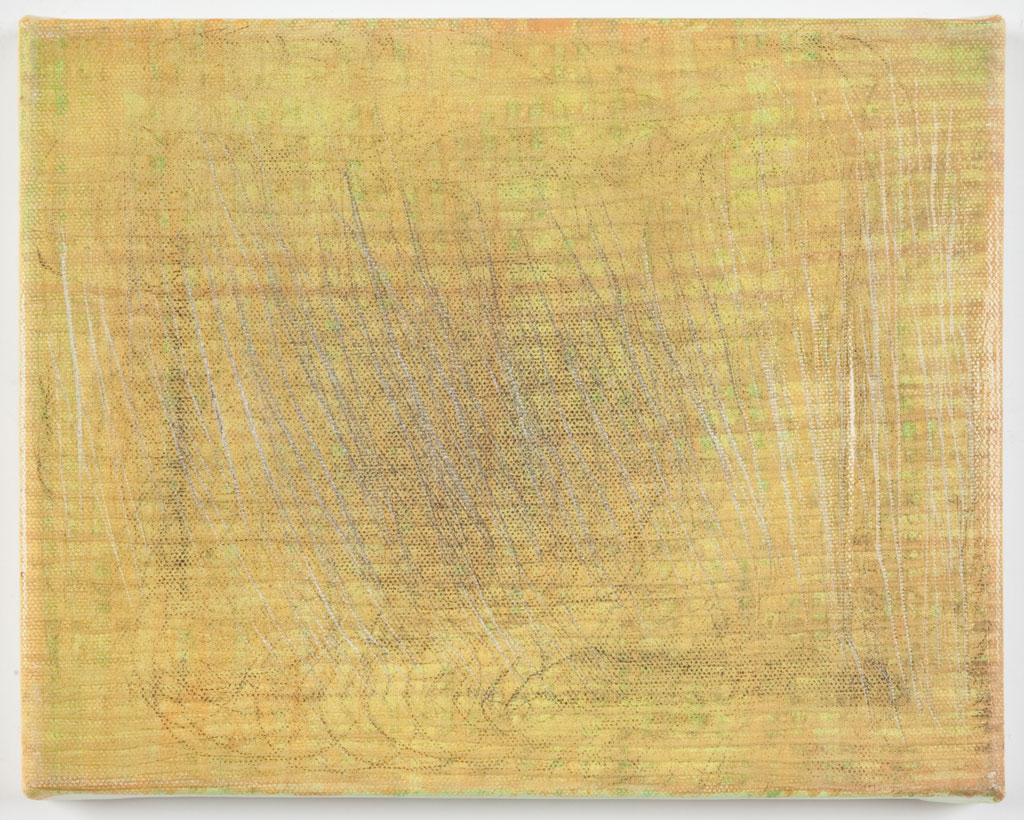

(Courtesy of A. Sortie, Inc. Nozomi Rose, ‘Happening’, 2012. oil on canvas. 8″ x 10″)

(Courtesy of A. Sortie, Inc. Nozomi Rose, ‘Happening’, 2012. oil on canvas. 8″ x 10″)

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: You participated in the Japan’s Earthquake and TsunamI 2011 art-project, could you tell me more about it?

NR: I was an organizer for Silent Art Auction and a curator for Charity Art Exhibition, but they were both student-driven projects. Our students learned a lot by carrying out those charity art events. I was just a tool for them to communicate with the College and Japan. Students who wanted to show and sell their art for their fundraisers, first on campus and then in a Chelsea art gallery, got together, and through myself, they were able to even have a commercial gallery owner donate his space for one day, for free.

We see those activities as our students’ educational experiences as well as healing processes. As a result, affected students successfully survived the crisis and graduated. I just presented on this theme with two other Professors, Kyoko Toyama in College Discovery/Counseling and Tomonori Nagano in Education and Language Acquisition, at the Opening Session at LaGuardia Community College: (For more details, look the website: http://www.lagcc.cuny.edu/Opening-Sessions/Workshops-II/)

Our College President Dr. Gail O. Mellow has been sympathetic about what Japanese students went through due to the unfortunate disaster, so she briefly came to our presentation. I felt her attendance symbolized a kind gesture by the College to the affected population in Japan.

The title of our paper is “Respecting Tradition and Creating a Community: Culturally Appropriate Response to the needs of Japanese Students and the College in the aftermath of Japan’s Earthquake and Tsunami.” We previously presented the same research in a session under the same title at the 2011 Asian American Psychological Association Conference in Washington D. C.

Firstindigo&Lifestyle: Then, I am always curious what an artist like you holds for their future. I guess it is about the dreams, what are your dreams and future plans?

NR: Wow, this is an interesting question. My dreams:

1) Sending 1000 young women from the disaster areas of Japan to New York City to study visual arts at LaGuardia Community College. This can be for three months or longer like two years. They do not need to be all Japanese citizens and I believe this is the right way for us to start spending more money on women’s education. This art project is after “Fairytale” by Ai Weiwei. Please let me know if you know anyone who would be interested in funding this project!

2) Creating a visiting East Asia artists and curators’ lecture series where people from various East Asia countries peacefully collaborate. After 3/11, my school suggested me to create an East Asia art course, so I wrote and proposed HUA191: the Art of Eastern Asia. It is now part of the College’s official course offerings. We are currently developing a new East Asia/ Japanese major, in collaboration with Queens College, so the new East Asia art course is becoming a permanent addition to the major. This is a bold step for diversity in the arts of Long Island City, Queens/ NYC. The next logical step would be an art lecture series with the same theme.

Future plans

1) To film “Dai Dai.” The title of my exhibition came from a film project that I started in 2010 entitled, “Orange.” Daidai is a Japanese word for one specific shade of orange, whose sound also connotes the concept of genealogy. The film content was mainly about my personal experience with the color orange, the largest earthquake in Japan, which was the Kobe earthquake before 3/11, and the sarin gas attack on Tokyo Subway system. I think production of a contemporary Japanese folklore was my initial purpose of this project. The tsunami earthquake was literally a life altering experience for me as an artist in part because it forced me to stop writing this script, but I recently decided to re-start it by re-structuring the entire work.

2) Swan Hill Art Biennale. I am helping the Swan Hill Museum of Contemporary Art in Himeji, Japan, to create an art biennale. Himeji literally means “Princess Road.” It currently promotes art made by women and I want to eventually include transgender women. For that, I think the conservative region needs a good woman’s medical center. We want a feminist art “museum-medical center,” so I will start talking to artists and doctors who may be interested in this type of project. This can sound very different from what I have done in the past, but I think the fundraisers for Japan last year were really about helping to raise funds for medical treatments.

3) Interdisciplinary Art Practices Conference in NYC. I am planning to organize a conference where artists and scholars who have more than one practice present their work and discuss how one discipline informs another one in their own practice.

4) E-Publication. I am writing an e-book for Tatsu-zine Publishing (http://tatsu-zine.com/) in Tokyo, Japan. This will probably be about Art-in-NY for non-majors and online art learning tools because this Japanese publisher specializes in e-books for computer programmers.

(Courtesy of A. Sortie, Inc. Nozomi Rose, ‘One Summer Dream’, 2012. oil on unstretched linen)

(Courtesy of A. Sortie, Inc. Nozomi Rose, ‘One Summer Dream’, 2012. oil on unstretched linen)

The artist’s website: http://nozomirose.com/

Information about the upcoming ‘Dai Dai’ -exhibition: Opening Reception: Thursday, Oct. 4th, 2012. 11:00 a.m. – 1:00 p.m, Discussion with the artist: Friday, October 5th, 2012, at 1:00 p.m.

http://www.ny.us.emb-japan.go.jp/en/i2/special_2012-10-02–31_DaiDaiExibition.html Opening

(Courtesy of A. Sortie, Inc. Nozomi Rose, ‘Happening’, 2012. oil on canvas. 8″ x 10″)

(Courtesy of A. Sortie, Inc. Nozomi Rose, ‘Happening’, 2012. oil on canvas. 8″ x 10″) (Courtesy of A. Sortie, Inc. Nozomi Rose, ‘One Summer Dream’, 2012. oil on unstretched linen)

(Courtesy of A. Sortie, Inc. Nozomi Rose, ‘One Summer Dream’, 2012. oil on unstretched linen)